On a dance floor in Leeds, a boy is losing himself to the beat. Head thrown back, shirt cascading off his shoulders, he bites down hard on his bottom lip, contorting his limbs into fierce positions. In Blackpool, two lovers cling desperately to each other beside the bass bins, their gaping jaws stretching out into a lusty peck as neon lights swirl around them. The revellers of Manchester, however, prefer taking to podiums, their abs poking out of slinky dresses and cut-off shirts. They are sweat-drenched and wide-eyed.

These scenes – visions of ecstasy, really – are a dime a dozen in the work of photographer Stuart Linden Rhodes, whose flashbulbs have illuminated all manner of dance floor antics since the mid-1980s. The photographer’s online trove of nightlife snaps – aptly titled Linden Archives – is a living, breathing capsule of queer clubbing in the north of England, offering a bolthole to a bygone era of Hi-NRG, leather waistcoats and the odd Take That club appearance. “Shirts would be off, sweat flying everywhere, people were away with the music,” Linden, 67, recalls of his clubbing heyday. “I’d be trying to get the right people in the right place and the right light, hoping the DJ wouldn’t put the bloody smoke machine on.”

He greets me over Zoom from a cosy front room in Harrogate, where he’s lived since the mid-’80s. Sitting in front of a vast bookshelf, in the frame behind him are two statement prints: a group shot of five big-wigged blonde drag queens and the cover of his debut photobook, 2023’s Out and About with Linden. The latter is a classic black-and-white affair, with the torso of a pre-TV-fame Louie Spence cutting through a crowd of leather armbands and studded masks like a chiselled forward slash.

Blackpool, Flamingos, 1995

It’s been a busy week for the photographer, whose mission to preserve the queer history of the north has just culminated in a smattering of prints being acquired by Manchester Art Gallery. Such good news comes just a month after the release of his second glossy photobook, Linden Archives, which takes the photographer across the globe to Pride parades, countryside drag luncheons and a party where Jean Paul Gaultier is inexplicably gnashing at someone’s pubic hair. Such is the life of a venerated lensman.

Linden’s initial foray into the art is a tale as old as time. “I’ve always liked looking at photographs,” he says, “What’s in them? How are they composed? What are they saying?” As a child, he would often sift through old family photo albums discarded in his local junk shop, some dating back to the Edwardian era, transfixed by these worlds so alien to his own. “I think it was the fascination of freezing a moment in time. It could be an empty street, but it’s the vehicles in it, the houses, the gates.” He likens it to the coachloads of tourists that descend on his native York every week, setting upon The Shambles – a winding, cobbled street crammed full of old-timey sweet shops and medieval whimsy – in search of some decadent, perhaps even romantic, flourish of the past. He wanted to replicate this feeling, he says, “but for the 20th and 21st centuries”.

from left: The artist James Stopforth dancing at the legendary Leeds club Vague, 1994; York, Milk & Honey, 1993

Entirely self-taught, Linden was always interested in capturing moments where a slight movement, the dropping of a stiff upper lip or a loosened shoulder, would reveal something hidden about his subject – a letting-down of the guard, so to speak. When it came to producing his own images, it would be no surprise, then, that he eschewed the controlled staging of commercial shooting in favour of the fleeting and ephemeral world of street photography, though in his case this usually constituted a sticky-floored basement.

Linden got his big break at the newly founded free gay magazine APN (All Points North) – “Right place, right time,” he smiles – working through the wee hours in exchange for free club tickets and a cab home on the company card. This was something of a novelty to the soon-to-be roving reporter, who admits he was never much of a clubber before being enlisted to document the comings and goings of queer clubland. In fact, his first trip to a gay club was at 19, a late blooming that he attributes to his rural upbringing in North Yorkshire. “That’s a northern thing,” he says. “I didn’t have a lot of time because I was working. I was late onto the scene – but I did make up for it.”

Leeds, Vague, 1994

And make up for it he did. A thorough reconnaissance into the local gay bars in northern towns big and small, most of which are now long gone, began soon after amid a blur of feather boas, writhing bodies and 12” Diana Ross remixes. His favourite night by far was the legendary Leeds party Vague, at The Warehouse. “I just loved it, it was so alien. People weren’t dressed in their Burton’s finest, or in bog standard Marks & Spencer, they were making their own costumes, wearing make-up,” says Linden. “It was [the same as] what had been going on in London, in the underground there, with Boy George and everything. And it had made it to the north – I couldn’t keep my camera away.”

At the time, club, bar and pub landlords were quickly cottoning on to a new class of punters known as DINKs (dual-income, no kids) and, coupled with the birth of the pink pound, the UK saw a boom in gay-specific locales across the country. Manchester – affectionately dubbed Gaychester – quickly emerged as the epicentre of this explosion in the north, boasting the likes of Paradise Factory (“a brilliant place to photograph”), the more mainstream Cruz 101 (“a bit more subdued in terms of fashion and dress”), Stuffed Olives, High Society, Hero’s and the storied night Flesh, which brought an air of the carnivalesque to The Haçienda’s midweek programming in the early ’90s.

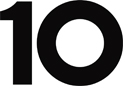

Brighton, Wild Fruit, 1993

Linden’s field reports ran the gamut of the scene, from Birmingham to Newcastle, thrusting him into crowds mixed with androgynous ravers, muscle heads, tat-gods, leather trade, spandex-clad exhibitionists and even the odd Joan Collins impersonator. “There were no mobile phones, the drink of the day was Red Stripe and cans of Breaker’s lager, and you could smoke indoors,” he says of the carefree state of his subjects, who dripped with sweat, hands held up to the sky. “I was capturing people who’d been in a full flight of emotion, away in a world of their own, at one with the music and the dancing,” he says. “Those have to be my favourite kind of pictures.”

The name of his Instagram account is a play on the title of his column for APN, Out & About with Linden, a pseudonym he chose in his days as a roving reporter. He adopted ‘Linden’ from his own middle name to protect his identity in the days of Section 28, a means of avoiding any repercussions that might have infringed on his role as a lecturer in business and hospitality management at Leeds Beckett University. “I had to protect my day job and my mortgage payment,” says Linden. He doesn’t consider himself a victim of Section 28, however, shrugging off such suggestions. “I managed to keep my career and my livelihood – I’m a survivor.”

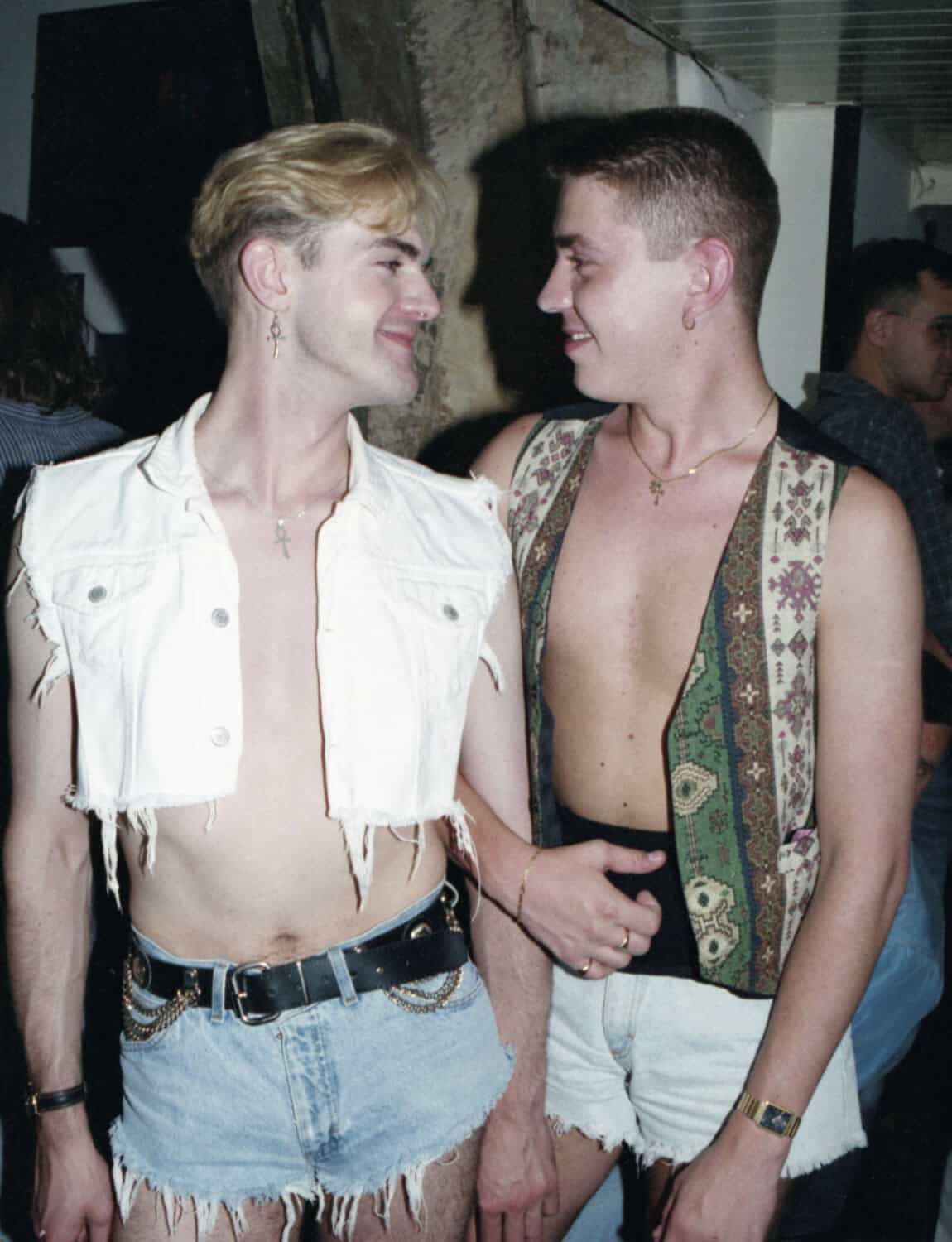

from left: Manchester, Paradise Factory, 1993; Blackpool, 1992

Birmingham, The Nightingale, 1992

Linden would stay at the paper until 1994, before moving on to Gay Times. By this point, the scene had changed drastically in response to Aids; the tunes had gotten harder, and so had the drugs. After doubling up on the first birthday of Liverpool’s Garlands and a night at Manchester’s Danceteria, Linden hung up his towel at the end of the decade, leaning into passion projects and his teaching work in the years that followed.

Establishing an archive, then, was never necessarily the plan for the photographer, but when Covid struck, a case of “insane boredom” and a sudden influx of spare time meant he could finally sift and scan through reams of his meticulously kept works. “It was a slog,” he says of the subsequent scanning, reformatting and tinkering that ensued over the next year. After finally getting on top of this mammoth task, the photographer soon had a far more daunting task on his hands. What the hell should he do with it all?

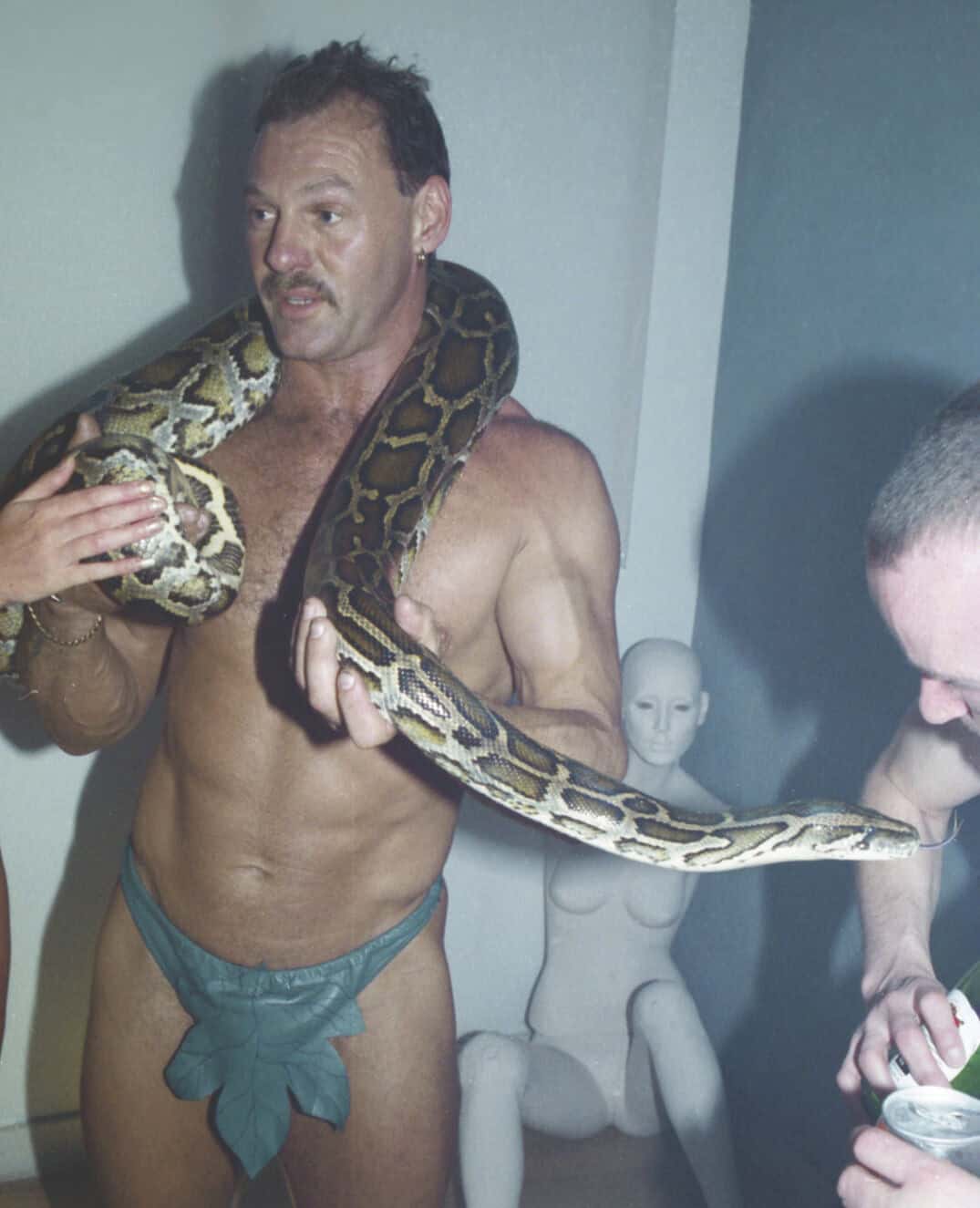

Scantily clad dancer, 1994

Figuring that these snapshots of bygone gay abandon belonged both to him and those who had sweated it out on the floor, Instagram felt a suitable destination for this mass of newly digitised work. He began posting daily on his account @linden_archives and after a few weeks found an audience not only in his fellow memory-lane-dwelling clubbers, but an entirely new generation of younger queers keen to explore their country’s history. Included were time stamps, locations and sometimes even anecdotal comments from those who lived these scenes, belting out the chorus of Divine’s 1984 banger You Think You’re a Man at Newcastle’s Powerhouse or dancing alongside a topless snake charmer in some dingy room on Princess Street in Manc city centre.

Journalists soon came knocking and, after one interview, Linden recalls being asked where a book of all this history was. Without an answer to give, work on Out & About with Linden: A Queer Archive of the North soon began. Admittedly unsure at first, Linden knew his work was on the right track when a Kickstarter aimed at funding the project exceeded its fundraising goal by several thousand pounds, the book itself selling out quickly soon after. Now two years older and wiser, he returns with Linden Archives, which explores queer public life outside the club, traversing marches, galas and events. “It’s been a labour of love and a very difficult birth, but we knew when we started that it needed a different perspective,” he says. “Some people have described it as a very sexy book, and there is a lot more semi-naked flesh, but I’ve purposefully kept it away from the top shelf.”

Marylin and friends at the ‘Gay Times’ 200th Edition Party, London, 1995

Preserving this spirit of “gay abandon” has always been a goal of the photographer, but this glosses over the his frustration with the repercussions of neglect. You’ll notice that prints from the Gay Times years are absent from his collection, at least in their full glory. After attempting to recover the original copies of his work, Linden heard from various sources that, over years of the magazine’s continually changing management, the archives were eventually lost to the rubbish heap. “They literally threw everything in black bin bags,” he says, still very much in disbelief, “negatives, photographs, films, paper, anything, and sent it all to the skip.”

Conscious that none of his family members would be much interested in his negatives in the event of something unexpected, Linden’s end goal is to find a suitable home for his vast archive, not only where it takes place, but where it belongs: in the north of England. “The best thing to do is to make sure that it’s secure and doesn’t get lost again,” he says. “It’s nothing personal against the south, but there’s not a queer archive of anything in the north. We have little bits in this library, little bits in that art gallery, but nothing central. There’s so much queer history here, and it needs recording.” In that case, we’ll let Linden lead the way…

Photography by Stuart Linden Rhodes. Taken from 10 Men Issue 61 – MUSIC, TALENT, CREATIVE – on newsstands now. Order your copy here.